Unit Overview

It is hard to call any Civil War regiment an “elite” regiment, but among the top contenders for such a title has to be the 83rd Pennsylvania. Their proficiency in drill, and steadfastness in battle forged a reputation that has few rivals in the annals of the Civil War. This reputation was sealed in the blood of 435 of their men who died in their 4 years of service, the second highest number of dead for any US regiment in the war. In a rare occurrence, the majority of their dead fell in battle rather than to disease, a further testament to their steadfastness and courage.

Research

Regimental History

When President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion in the spring of 1861, nearly 1,000 men from Erie, PA responded to the call and formed the 90-day Erie Regiment. This first regiment from Erie never made it farther than Pittsburgh, PA – where they spent most of their time carving rings from shells they found on the riverbank – before their enlistment expired and they were sent home. Immediately after returning, though, John McLane immediately requested permission to raise a 3-year regiment from Pennsylvania’s governor, and was given the go-ahead. McLane set-about raising what would become the 83rd PA right away.

On September 13, 1861, men from Erie, Crawford, and Forest counties in Western Pennsylvania. After mustering in Erie, PA, the new regiment was immediately sent to Harrisburg and then on to Washington where they were assigned to the 3rd Brigade under Dan Butterfield in Fitzjohn Porter’s division. Initially the regiment was clad in whatever civilian clothes or Erie Regiment uniforms they had at home, and humbly dressed they set about becoming experts in the art of soldiering. By October, though, their initial clothing had begun to wear out, so Colonel McLane requested new uniforms, and they were initially given New York state jackets and kepis, along with issued trousers.

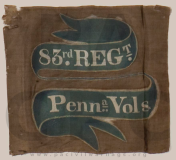

Throughout the fall of 1861, the 83rd PA continued to drill, with both Colonel McLane and the newly promoted Lieutenant Colonel Strong Vincent proving to be hard-nosed drill masters. By November of that year, their division was reviewed by General George McClellan with the goal of selecting the best regiment from each brigade to receive special French imported chasseur uniforms. At this review, the 83rd PA proved to be the best of their brigade and thus were issued the imported uniforms. While these new uniforms (which included everything a soldier could need, head to toe) cut a dashing military appearance, Colonel McLane was very concerned about their functionality on campaign in VA. Thus, while they are famous for this uniform, aside from knapsacks, fatigue caps, canteens, and their hooded talmas; all the chasseur uniforms were left in storage in DC, and the men were never reunited with them.In April 1862, the 83rd moved with their brigade (now part of the new V Army Corps, Army of the Potomac), to Fort Monroe to begin the Peninsula Campaign.

The early stages of the campaign were more monotonous than eventful for the 83rd.The slogged through mud and rain to Williamsburg and helped construct the siege works they would, for the most part, never be used. The only eventful experience for the 83rd during this time was when half the regiment was sent across the James River to raid a plantation owned by a known secessionist with the goal of arresting him.This expedition was commanded by Strong Vincent, and was a night-time raid. As the regiment advanced on the property, they noticed movement in the shadows; some of the more nervous men fired at the shadows before the regiment was ordered to charge the house. As they dashed towards the house, a large group of people was seen retreating towards the river, and the 83rd proceeded to follow. As they closed with the crowd, expecting a fierce hand-to-hand fight; they were shocked to discover the crowd was made up of dozens of enslaved men and women who lived on the farm. The regiment was immediately halted, and once the confusion was sorted out, the enslaved families treated the men of the 83rd to a feast before they returned to the boats and went back to camp.

In June 1862, the 83rd got their first taste of combat at the Battle of Gaines Mill. As they crossed the river, the regiment was ordered to drop packs and haversacks before being sent to the Federal right. They fought all day, holding off repeated Confederate attacks. At one point during the fight, a ceasefire was called and both sides sent a representative out. The Confederates acknowledged the 83rd’s fighting ability, and asked them to surrender rather than suffer more. When asked by the 83rd’s representative where the Confederates were from, they responded “South Carolina.” The 83rd officer shouted they would never surrender to South Carolinians, and turned and ran. The Confederates opened fire, killing the officer, which them prompted the 83rd to return an intense fire. Late in the afternoon, the V Corps was ordered to retreat, and the 83rd was the last regiment to retreat across the pontoons…leaving all their knapsacks and haversacks behind. For the remainder of the retreat to Harrison’s Landing, the 83rd would rely on the pity of other regiments for their food and shelter. In this battle, the 83rd lost their beloved Colonel McLane, and Strong Vincent took over the command. Unfortunately, Vincent was took sick with malaria to command for long, actually passing out on his horse while trying to lead the regiment, forcing him to be sent home to Erie for recovery.

At Gaines Mill, the 83rd lost 50% of the men they took into battle, leaving them with around 250 men in the ranks. A few days later, the 83rd would again see action at Malvern Hill where they fought supporting a US artillery battery, helping them fend off repeated attacks from a Confederate Louisiana brigade. By the end of the day, the 83rd lost nearly 50% of what was left, leaving them with around 140 men. A few days later, they arrived at Harrison’s landing, having lost over 300 men in 2 battles and survived for a week on the extra rations of other regiments who took pity on them. Despite this, the regiment remained motivated and eager to continue fighting, which they wouldn’t have to wait long for.

In the summer of 1862, the V Corps was sent to join John Pope’s army in what would become the 2nd Manassas campaign. At the end of August, the 83rd participated in the Battle of Second Bull Run, participating in the V Corps attack on August 29th, once again losing nearly half the number engaged with 20 killed and around 60 wounded. By this time, the regiment (which went into action in June with 550 men) numbered barely 100 men once some of the wounded from the Peninsula returned. In September, the 83rd was held in reserve at Antietam, which for the exhausted Pennsylvanians was absolutely necessary. Numbering barely 100 men, nearly ⅓ of the regiment lacked functional rifles, and almost everyone was missing 1 or more pieces of equipment. It would take time for the regiment to recover from the summer of 1862.

After Antietam, the 83rd was sent to Warrenton, VA to rest and recover while waiting for McClellan or Lee to make a move. In November that move came, and the 83rd joined Burnside’s army in their advance on Fredericksburg. On December 13th, once again led by Strong Vincent, the 83rd joined their brigade in the assault on Marye’s Heights as one of the last brigades to attack as the sun began to set. They would spend the next day and 2 nights camped in the cold fields below the stone wall, surrounded by the dead, dying, and wounded of the fighting on the 13th before they were pulled back across the river and into winter quarters.

The winter of 1862-63 was spent rebuilding the regiment and training new recruits. Colonel Vincent once again had to return home after his malaria–which he never fully recovered from–returned while in camp. By the start of the spring campaign, the 83rd would number roughly 400 men. In May 1863, the 83rd would see very limited action at Chancellorsville as their corps was held in reserve for most of the battle. After the battle, the regiment returned to its former camps across the river from Fredericksburg.

In June 1863, the Army of the Potomac set out to chase Lee’s army north, ultimately resulting in the Battle of Gettysburg. As the Army went through some reorganization, Colonel Vincent was promoted to brigade command, and Captain Orpheus Woodward would lead the regiment in battle. As they neared the Pennsylvania border, Vincent ordered the tattered and torn colors of the 83rd uncased, proud to have the colors of his regiment return to defend the soil of their home state. On July 2nd, the 83rd formed the center of Vincent’s line on Little Round Top at Gettysburg. To their left, the 20th ME fended off repeated attacks from two Alabama regiments while the 83rd and 44th NY to their right fought off the 4th Alabama and 1st Texas regiments. The 83rd, fighting in the woods and behind barricades, suffered lightly in this battle losing 55 men. The biggest loss, however, was their brigade commander, Strong Vincent, who was shot through the groin while rallying the faltering 16th MI of his brigade. Vincent would live five more days, dying the same day as the notice of his promotion to brigadier general arrived at the field hospital he was staying in.

Following Gettysburg, the 83rd would be part of the constant movements and smaller battles between the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia. They were lightly engaged at Mine Run in November-December 1863, before finally going into winter quarters at Culpepper, VA. Much like the previous winter, the 83rd spent the winter months recruiting and training new recruits. In addition to 169 men who reenlisted as veteran volunteers to take advantage of the reenlistment bounty and furlough, the regiment received nearly 400 new recruits and returning wounded, bringing them up to around 700 men for the spring campaign.

The spring of 1864 dawned warm and sultry in central Virginia. In early May, the Army of the Potomac set out on what would be one of the final campaigns of the war. The rejuvenated 83rd crossed the Rapidan River on May 4th, and marched headlong into the dense forest of the Wilderness. On May 5th, the 83rd would lead their brigade in the assault on Saunder’s Field, their right resting on the Orange Turnpike. They, and the 20th ME following behind them, would be one of the few regiments to break the Confederate lines that morning. After a fierce fight, they were forced out of the Confederate lines, leaving many dead and wounded behind. One of those who fell was Sergeant Alex Rogers, the color sergeant who had carried the state colors since Gaines Mill. The state colors were briefly captured in the confusion of the retreat, but were quickly rescued by men from the 44th NY who returned the flag to its owners once they reached US lines again. For the rest of the day and throughout the 6th, the 83rd engaged in sporadic firing and skirmishing, but made no further assaults on the Confederate lines. During the fighting on May 5th, Colonel Woodward was badly wounded, and Lieutenant Colonel McCoy took over command of the regiment.

On May 7th, the 83rd and the rest of the Army began sliding south to Spotsylvania Courthouse where Grant planned to bring Lee to battle in the open, away from the Wilderness. Unfortunately for the men in blue, Lee’s cavalry and Anderson’s Confederate infantry division beat them to Spotsylvania, and on May 8th the 83rd went into action at Laurel Hill. Unlike the intense preparations and planning before the Wilderness assault, the assault on Laurel Hill was piecemeal, with General Warren throwing his corps’ brigades into the attack one or two at a time. Because of this, the dug-in Confederates were able to chew up and throw back each brigade one after another. Once night began to fall, the armies began settling into trench warfare.

From May 9th until the 20th, the 83rd Pennsylvania was regularly engaged in the battles around Spotsylvania. On May 12th they helped pin down the Confederate 1st Corps forces as Hancock’s II Corps attacked the Mule Shoe Salient. They would act as a diversion for the May 18th assault, and participated in numerous skirmishes around Spotsylvania. By May 20th, the V Corps began the next movement south, around Lee’s army, and the 83rd began their march away from Spotsylvania.

The regiment again saw action at the North Anna River, where their corps was nearly destroyed by a well-planned trap set by Lee, but with Longstreet wounded and Hill and Ewell both ill, Lee was left to manage his corps himself. However, Lee was also ill, and on the day he was set to spring the trap, he was too ill to leave his tent, and the planned attacks did not go as intended. On the 27th, as Confederate troops advanced on Sweitzer’s Brigade, the 83rd and 16th MI were sent to their support, and found themselves squarely on the flank of the rebel attack column. Colonel McCoy ordered several companies into line and they attack the Confederates, killing and wounding many, and capturing nearly 1,000 prisoners along with the other regiments around them. One member of the 83rd captured Colonel Joseph Brown, the rebel brigade commander, by “seizing Brown by the collar, and dragging him into our own lines” (Bates, p. 1257).

After the fighting at North Anna River, the 83rd spent most of the rest of the summer campaign engaged in skirmishing and digging trenches, before finally settling into the siege works around Petersburg. They were involved in many of the railroad destruction operations, especially Jerusalem Plank Road and Peeble’s Farm. On September 18th, the term of enlistment for the 83rd expired, and about 100 of the 350 men in ranks went home. The remaining soldiers reenlisted (if they were veterans), but the new strength was not enough to main the regiment, so they were redesignated the 83rd Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Battalion, and command went to Captain C.P. Rogers.

In December 1864, the 83rd was heavily involved in the Weldon Railroad, after which it went into winter quarters along the Jerusalem Plank Road. During this third winter quarters, the 83rd received four brand new companies of recruits, bringing the strength of the regiment nearly up to full regimental strength, and giving promotions to all the senior officers of the regiment. In February 1865, the regiment was again hotly engaged at Hatcher’s Run where they suffered heavy casualties. After this battle they returned to camp until the start of the spring campaign in late March 1865.

Beginning on March 29th, the 83rd was heavily involved in numerous battles and skirmishes leading to the surrender of Lee’s army on April 9th. At Jones’ Farm, White Oak Road, Gravelly Run, Five Forks, Sutherland Station, Jettersville, and the final pursuit to Appomattox; the 83rd continued to equit itself with the same courage and determination they had shown on the fields of the Peninsula and the rocky slopes of Gettysburg. After the surrender at Appomattox, the 83rd moved with their army to Washington, DC for the Grand Review, where it was mustered out of Federal service on June 28th. From there the regiment traveled to Harrisburg, PA where it was disbanded, with all the veterans and recruits returning to their homes throughout the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

The 83rd Pennsylvania was one of hundreds of regiments that fought in the Civil War, and one of over 200 fielded by their state alone. By the end of the war, only the 5th New Hampshire surpassed the 83rd in total number of men killed or died of disease. Of the 2,270 men who served with the 83rd Pennsylvania, 435 of them died – 278 killed or died of wounds, and 152 to disease. In addition to this, 514 men were wounded, and several hundred captured, losing more than 50% of the men who served in the ranks of the 83rd. Few regiments on either side can boast a record as distinguished as the 83rd Pennsylvania. The regiment had to be rebuilt no less than 4 times throughout the war, and at times fielded barely 100 men, but continued to serve with distinction despite the losses. While they are famous for their flashy uniform of 1861, their blood-soaked reputation as a combat regiment was forged wearing the simple blue uniform of the American soldier. While they lack the fame of other units like the Iron Brigade, Irish Brigade, 26th North Carolina, or other notable units; their legacy is one of courage and steadfast dedication to their country, almost unequaled in the pantheon of Civil War regiments.

Helpful Reading

Impression Guidelines

Introduction

Though the 83rd is famous for being one of the 3 regiments given the French chasseur a pied uniform in 1861, they never wore it in combat and by 1864 any vestiges of that uniform were long gone (except maybe a few fatigue caps-bonnet de police-floating around among the veterans). They were a veteran regiment, and would have looked like any other unit in the Army of the Potomac. What set them apart was their experience, the charisma of their leaders, and the metal they were made of. Few regiments can claim to have as solid a reputation as the 83rd. So, while we won’t be flashy like zouaves, or have the iconic headgear of the Iron Brigade, know you’re representing a truly elite regiment from the Civil War. (The guy circled in the Massaponax Church photo is Leander Herron of the 83rd who would go on to win the MOH in 1868 for an engagement near Fort Dodge in Kansas.)

All uniforms and gear should be constructed using proper materials and methods.

Impression Guidelines

Headgear:

- Issue forage caps

- Commercial forage caps and kepis

- Black felt civilian hats in limited numbers

- Everyone should have a red 5th Corps badge, but company letters, “83” and “83 PV” brass are also acceptable and encouraged

- Chasseur fatigue cap (bonnet de police) may be worn around camp

Coats:

- Schuylkill Arsenal Infantry Jacket (many veteran regiments received these jackets in the spring of 1864)

- Private purchase jacket (these were especially popular among the 83rd in 1864)

- Lined or unlined sack coat (SA or Contract)

- Commercial sack coat

- Frock coats are discouraged

- NCOs should have proper rank insignia

- Veteran stripes can be worn in limited numbers on jackets, frocks, and commercial sack coats but NOT issue sack coats (169 men reenlisted before the campaign began)

Trousers:

- Sky blue SA or Contract trousers

- Sky blue commercial trousers

Shirts and drawers:

- US Army issue shirt or contract issue shirt

- Cotton or wool civilian shirts of proper construction

- US Canton flannel drawers

- Civilian drawers of cotton, flannel, or knit materials

Footwear:

- US issue brogans

- Civilian brogans (no camp shoes)

- Boots

Accouterments:

- US issue belts (leather keeper or brass keeper)

- US issue cap pouch

- US Issue .58 cal. Cartridge box with plates (slings optional and generally discouraged)

- 2 or 7 rivet US bayonet scabbard

- Painted cloth US issue haversack

- US issue double bag knapsack preferred, blanket rolls accepted (this is still early in the campaign, and the 5th Corps was photographed before the Wilderness with pretty full knapsacks)

- Philadelphia or NY Depot canteen with correct cord or chain and stopper with cotton sling

Blankets and Tentage:

- US Issue blanket

- US issue ground cloth preferred, ponchos accepted

- US Issue shelter tent half

- Foot pattern overcoats if you think you’ll need it

Rifles (must have fitting bayonet):

- 1861 Springfield

- 1855 Springfield

- 1863 Springfield

- P53 Enfield

- 1842 Springfield if that’s all you have

When packing, remember this is a veteran regiment, but they also had many, many new recruits. They started the campaign with around 700 men, after having been rebuilt as a regiment several times already in 1862 and 63. So, you can portray a veteran or a brand new soldier to the Army.